Why do women from the Northern Triangle countries of Central America risk their lives along with their children’s, traversing through the treacherous, dangerous Mexican corridor, full of chaos and not knowing if they will live another day, if delinquents will steal their last peso, hurt them, or kill them? Why do they take the chance in full knowledge that they may not ever make it to the US/Mexico border?

As I listened to their intense, heart wrenching stories, explaining why they had decided to leave their home, their families, and their country, I realized that an underlying emotion racked their entire well- being: in their narratives were inherent pleas for “help,” for themselves and their children. In fact, many of the women seemed to be trauma victims although they had not been properly diagnosed and treated for lack of specialized care in the detention facility.

I worked with dozens of women during a six-month span. In the process, I started to analyze the emerging themes: some were victims of domestic violence, others of gang violence, but all of them feared for their lives and/or their children’s. All of the women stated emphatically that they could not return to their home countries for fear of persecution, which meant that if they returned they would eventually be killed.

The Women’s Stories

For purposes of this writing project, I selected the narratives of seven women: three from El Salvador, three from Honduras, and one from Guatemala. Each story presented herein is a dramatization, an account based on the information they shared with me. Basically, these stories are factual, as they related the facts to me, in individual interviews that lasted approximately one hour. We were not allowed to tape record the interviews, therefore, I relied on my brief notes and memory to develop each story and, upholding each one as genuine and true, as much as possible, and in accordance to what they had shared with me. Naturally, the collection of stories is used as representative of the women’s experiences and provide only a small window to the multitude array of suffering and tragedy that have impacted each woman, indeed each family.

Sharing Their Stories and Their Pleas for Help

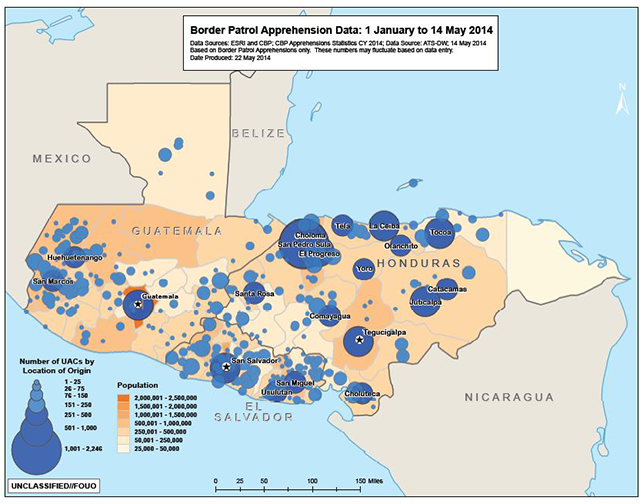

Very few people in our country understand the plight of the Central American migrants, specifically, why thousands have sought to cross the US/México border seeking to start a new life, sometimes as legal residents, but mostly, as undocumented workers. When the news that thousands of unaccompanied children from Central America were migrating to the U.S. became a crisis in the summer of 2014 (see article by Domínguez-Villegas), many people were surprised, and even disturbed by the numbers. Approximately 51,000 unaccompanied children were apprehended at the U.S./México border in fiscal year 2014. The numbers have since declined but then, increased, although not at the level seen in 2014 (see Rosenblum and Ball, Trends in Unaccompanied Child and Family Migration). However, the majority of Americans were not interested in their stories of migration, even though there were people who cared and gave the migrants some humanitarian care. But, the opportunity to learn about the migrants, especially the young families who risked their lives and gave up everything of their past, was lost and then, forgotten. The intent in publishing their stories is to inform, educate, and bring about the awareness and conscience of who we are as Americans living in a democracy where people are crying, pleading for our help, right outside our doorstep. Or, quite simply, my main purpose is to give “voice” to the voiceless.

The Title

The title, “In the Shadow of the Half Moon,” has a twofold reference. ‘Half Moon’ is a metaphor for the youthfulness of the women, and are seeking a new life to accomplish their lives’ goals, or to fulfill the rest of their lives in a safer space, perhaps, better, if not for them, then, for their children. The metaphor also describes the uncertainty of their future in the United States. Upon arriving at the border, the women’s emotional states are uplifted, and the reality of having to start all over again in a new world has not yet leveled to a reality. However, in the ensuing days, after their asylum process is motion, the uncertainty of what their future holds for themselves and their children becomes a source of anxiety. No matter how much they’ve struggled to reach the border, their encounters with conflict are far from over, in fact, they are replaced with new battles, problems, tribulations, and there’s a long, uphill process to become a citizen of the United States. Finally, the moon signifies “in the cover of darkness,” which brings to mind the fact that most of the women left their homes for the US in clandestine circumstances so no one would suspect their departure.

The Stories and Supporting Documents

The following section includes the women’s stories, titled according to their names and home countries; of course, the names are fictitious to protect their identities. The stories contain the heart of what the women related to me thus, their brevity is focused on providing the reader with a friendly-readable format. Furthermore, at the outset of each story, I include an introductory summary that pulls the reader into the main narrative. Following this section, I include background information for the purpose of providing a contextual base to further explain the actions of the women.

El Salvador

Katarina

Summary: Katarina was threatened by the leader of the MS in her vicinity, known as “el crazy,” and demanded that she must comply with his sexual advances or else he would kill her two children, ages 11 and 3. Katarina was living with her father and her two children while her husband, in the United States, worked to support the family. Then, her father died, and knowing that she was alone but receiving money from her husband, the MS leader began to threaten her. She moved in with her mother, reported her case to the police and then, on Dec. 25th left El Salvador for the United States. The police told her that she should leave for her own safety and her children’s, since they wouldn’t be able to help her immediately. If she returns, she feels that the MS leader will kill her.

Katarina’s Story

The day that Katarina’s father died, her world turned upside down. “El crazy,” the ranking leader of the area’s MS (Mara Salvatrucha) had had an eye for her for some time now, and he knew that she had a son, age 11, and a daughter, 3 years-old. He also knew that her husband was in the United States and sent her money for living expenses every month.

Katarina wept incessantly at her father’s funeral. Her life had become increasingly difficult ever since her husband left for the U.S. Neither wanted the separation but making a decent living in her hometown is extremely difficult if not, impossible. Her father had been the anchor in her and her children’s lives. But now, his departing left her defenseless, and “el crazy” wasted no time to make his move and claim Katarina, the beautiful young woman, as his own mistress.

The grief she poured over her father was also rooted in self-pity and fear. Soon afterward, her worst fears became a reality. “El crazy” begin to call her, at first politely but then, aggressively. Katarina managed to keep him away by repeating her pleas to respect her marriage to the father of her children. But nothing deterred “el crazy” since he wanted to possess Katarina as a symbol of his prowess as a powerful cartel leader. He begins to threaten her, warning her that he would kill her children if she didn’t comply with his wishes. But Katarina would rather he kill her than her children, but by killing her doesn’t mean that he wouldn’t also kill her children.

Threats from a gang, any gang, usually target the children of their victims, hurting them where they are most vulnerable.

Despite the constant phone calls and harassment, Katarina managed to keep him at bay, but she knew that it was a matter of time before he would force himself into her life. After about a year, Katarina made her move. Christmas day was a natural distraction, so around that time, she moved out of her house, quietly, without anyone noticing. She moved into her mother’s house, reported her case to the police, and then, on December 25th she left El Salvador for the U.S. The police could not protect her from the powerful MS cartel leader who yielded perhaps more power than the police force. She was advised to leave the country, the police admittedly said to her that there was nothing they could do to help her immediately.

Katarina collected a few thousand dollars from her mother, her uncles, and her aunt. But she couldn’t take both of her children, so she chose her 3 year-old Adelia, and asked her sister, Rosa, to take care of 11 year-old Daniel Ricardo. Her sister had recently moved to another house so no one knew where she lived but she feared that the gang members would eventually find her sister and her son.

Katarina Met “El crazy’

One way a gang leader shows off his rank is by collecting girlfriends or mistresses. “El crazy” singled out Katarina because of her attractiveness, and although she ignored him she feared him. While she acted politely to his advances, she didn’t give in. The gang leader would have destroyed Katarina instantaneously if she had outright rejected his advances. Everyone knows the rule: if you reject the advances of an MS leader, you will be killed. Death is the penalty for all rejections: for refusing to join the gang, for refusing to pay “renta” or “cuota,” and for refusing to become the girlfriend or mistress of a gang leader.

Rosa, Katarina’s Oldest Sister

Rosa is a single mother of a son, Carlos José, just a year younger than Katarina’s 11 year-old. She knows Katarina’s desperation and the gang’s threat had to be taken seriously. Her boyfriend has asked Rosa to move in with him and she decides to do so as long as he accepts Katarina’s son as well. The agreement is a relief for Katarina since she feels that he will be safe with both of them, at least for a while.

Living in Constant Fear

Families caught in the web of threats and fear are constantly on the move, risking their lives, and even taking a gamble for even a small mistake can cost them their lives, and the lives of their families.

Such was the case of a family of four that lived in the same neighborhood as Katarina and her father. The father owned a small corner store in their home, selling a variety of goods and groceries. They were targeted by the MS and demanded monthly payments (renta). The family struggled to make ends meet, and the father did an unimaginable, unacceptable gesture to the gang by refusing to pay such an exorbitant amount of money that he could not afford. It was a mistake that led to his death as well as his wife’s and two sons. They were massacred by a dozen members of the MS gang, their bullet ridden bodies were found inside their home. The cold-blooded killings were the crass warning to others who dared to refuse the gang’s demands.

El Salvador

Maribel

Summary: Maribel was raped by three members of the Maras gang. She was threatened with death to her and her family if she told anyone about the rape. Maribel didn’t tell her mother, but her mother immediately sensed that something was wrong due to Maribel’s depression and suicidal tendencies. After her mother learned about the rape, she called the police but received no assurances. Police expected payment for the protection or they were also threatened by the Maras. Maribel felt that she couldn’t return to school or even leave her home because the Mara gang member, Clarisa, continued the death threats and began to physically hurt Maribel. Then, after Maribel was badly beaten, her mother made the decision to leave their country and migrate to the United States.

Maribel’s Story

Maribel was excited to return to school after a month-long Christmas vacation. At fifteen, she was determined to finish her high school program and continue her studies; maybe, become a nurse. Among the new students at her school one of them seemed to be very friendly with Maribel. She was Clarisa, a year younger than Maribel and seemed quite eager to make many new friends regardless of their ages. But actually, Clarisa was more interested in recruiting her classmates into the Mara gang, which she had joined a few years ago and was now a ranking female member. Typical of her group’s expectations she had to prove her worth by out-maneuvering her male counterparts. But Maribel refused Clarisa’s invitation to join.

Clarisa managed to entice several of Maribel’s classmates into her circle. Soon they would be among the many adolescents roaming the streets of their tightly knit community causing even more despair amongst their families already disconcerted over the rise of violence in their midst. Their hopes and dreams for their children have been shattered as they watch their beloved sons and daughters become consumed by the illicit drug culture.

Clarisa would not accept Maribel’s rejection. She threatened Maribel with consequences: physical aggression, rape, and hurting her family members. Clarisa and her recruits used social media to pressure Maribel but her resistance was firm, which annoyed and frustrated Clarisa.

Even though Maribel tried to avoid Clarisa, it seemed that she was following her and appeared at every corner she turned.

It was pouring rain when Maribel walked home from school one day in April. She decided to take the paved road instead of her usual shortcut through residential alleys. Clarisa and three male members of the Mara spotted Maribel as they drove through the street. It wasn’t incidental since they had planned to find and sequester Maribel, and punish her for refusing to submit to their control. They forced her into their car and took her to an abandoned shed a few miles from the main road. Maribel, screaming and crying, couldn’t pry loose from their stronghold. They hit her in the face and stomach and ripped off her clothes. Each of the men took turns sexually abusing her, while Clarisa added her venomous verbal assaults, also kicking her while she lay helplessly.

Maribel feared for her life, but in moments of sheer desperation and excruciating pain, she wanted to die. The four finally let her go but before they left, Clarisa threatened her: “if you tell anyone about this, we will kill you and your family.”

But Maribel’s mother immediately sensed that something very bad had happened. Maribel locked herself in her room, refusing to go school and hardly ate and drank anything. Her depression was profound and serious and her mother became desperate to find out what had happened. After days of agonizing anguish and despair, Maribel, crying uncontrollably, told her mother, “they raped me and beat me.”

Maribel’s mother felt the immense pain in her daughter, and to her utter disbelief she noticed that Maribel had attempted to take her life by cutting into her wrists with blunt objects. How could she help her daughter and bring to justice what Clarisa and the other three had done to her? Her first step was to report the case to the school officials.

The school administrators would not take any action since the rape had occurred off school grounds. Next, she turned to the police, but they also refused her case citing a lack of proof or evidence. However, they would investigate her case provided they were compensated for their work. They were reluctant to step into a situation which clearly involved Mara gang members. The dominant and powerful force of the Mara gang had crippled the police’s abilities to even protect the town’s citizens.

Maribel slowly emerged from her depression. A few weeks following the rape she was still weak and vulnerable and not attending school to avoid any contact with Clarisa. But she felt strong enough to leave her house for a short walk to the store to purchase some essentials. She was one block from her house when the Mara gang members approached her from behind and cornered her. They had been constantly monitoring Maribel and were determined to hurt her again as they had warned her, in retaliation for denouncing, or attempting to denounce their crime against her. There were four gang members, wearing scarfs to disguise themselves, but Maribel recognized one of them as Clarisa. They knocked her to the ground, hitting her head and then kicking her stomach and back. Two bystanders yelled at them but fearing for their safety, refrained from becoming involved. Others joined in, shouting “to stop” beating the young girl that was noticeably hurt very seriously. They left, and Maribel, at the point of unconsciousness, laid along the side of the street writhing with pain and crying incessantly.

Her mother was at her workplace when she received the call from Maribel. When she saw Maribel, beaten, distressed, crying and screaming like she’d never heard before, she knew what she had to do. After a couple of weeks of collecting enough money for their journey, Maribel and her mother left their home quietly, when no one was watching them. They traveled across Mexico and then, turned themselves in to the authorities at the Texas/Mexico border.

El Salvador

Ramona

Summary: Stefani, age 14 and in the seventh grade, and mother, Ramona, lived in southeast El Salvador. On January 26, 2017, Stefani was approached by two Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) gang members wanting her to join their group. She refused. A few days later, Ramona opens the front door of her house and finds a dead man a few feet away. She and Stefani are traumatized; the dead man was from another colonia who had been reported missing but they never learned his name. Stefani realized that the dead man was a message from the gang that their death threat was real. Two months later, Ramona and her daughter were confronted by two other MS-13 members, repeating their death threat to Ramona, and pushed her to the ground. Ramona knew that the gang had “ordered” her assassination. If they remain in their country, they feel that they will be victims of death threats. There is no end in sight; the gangs (MS-13 and Barrio 18) are in constant conflict with each other and the police, and have near total control of many of the authoritarian structures.

Ramona’s Story

At daybreak on January 29, 2017, Ramona, a single mother of 14-year old Stefani, wakes up to the sound of a vehicle pulled up in front of her house. She heard a ruckus as if several people were yelling at each other. She ran to the front door, opened it and discovered a body, on the ground just a few yards away. As she walked toward the corpse, she realized it was a young man that had been thrown out of a car. She saw his legs and arms mangled and his torso riddled with bullet holes; an image that jolted her heart and spirit. She knew instantly that this killing was the gruesome work of the criminal organization that plagued her town. Stefani caught up with her mother and both cried in desperation. The neighbors approached the scene of the broken, bloody corpse. They didn’t know his name, but they knew that he was from another colonia and had been reported missing, and presumed dead.

Stefani had another thought. It was a message from the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), deliberately sent to her. A warning, she thought, that if she didn’t comply with their demands she would be the next victim. Or, maybe they would kill her mother instead.

Days earlier, on her way to school, Stefani had been approached by two MS members. They wanted her to join the gang, but Stefani brushed them off, telling them that she couldn’t do anything like that. MS gang recruiters are trained to target their victims and persist until they complied. They would not accept Stefani’s refusal; to do so would draw a harsh sentence from their boss, and death was always an option.

Stefani, pretty, slightly built and looking younger than fourteen, was the “innocent” one, the perfect type to coerce and become the “soldier” at the mercy of a powerful influence that would take her away from her family. The more she refuses, the more they would clamp down and insist that she meet their demands. Stefani knows that she must follow the rules: “ver, oír, y callar” (see, hear and be quiet). She knows the consequences for refusing to join them, and she could be killed like the young man they found in front of their house.

But Ramona suspected that something was wrong with Stefani. Stefani’s reaction to the corpse seemed overwhelmingly emotional, and she wouldn’t respond to her questions about what was going on. Ramona noticed that a particular car would constantly drive by in front of their house. She suspected that Stefani would be harmed so she decided to accompany her to school and back, everyday, keeping a close eye on her daughter.

Two months later, Ramona and her daughter walked back home from school when they were confronted by one of the gang members. He wanted to know what Ramona was doing, trying to protect her daughter. But Ramona acted with defiance and told him that it was her responsibility as a mother to protect her. The man became agitated and responded by pushing Ramona to the ground. She landed hard and her hip hit a large rock. She managed to get up, struggling with the pain, and again, stood steadfast in front of her daughter. The man told her that she could not keep her daughter from “them” and to continue resisting will lead to her end. Ramona knew that it was a “death threat” and she had only one other option.

That evening, Ramona and Stefani packed a bag of essential items and made their plan to “escape.” In the early morning hours on the first day of April, Ramona and Stefani went downtown, hailed a cab and began their journey north.

Honduras

Jenni

Summary: Jenni received a threatening message from a known powerful criminal organization or gang, which her ex-partner had had a leadership role. At the time they were together, her ex-partner deceived her, keeping secret the fact that, not only was he a gang leader but that he had “betrayed” his boss and had to go into hiding. She found out the facts when he turned himself into the authorities at a US/Mexico border checkpoint. Her ex-partner, the father of her young daughter, is now serving time in a US prison. He eventually reached out to her and apologized. She told a friend that she had communicated with him and soon afterward, she received the letter from the ex-partner’s gang boss, that in retribution for snitching, the gang would kill her children, which Jenni felt could also mean her death as well. She went to the police but their recommendation was that she leave immediately. The gang is very powerful in Honduras and beyond, and she had no doubt that they would find her.

Jenni’s Story

Jenni and her 3 year-old daughter, Yojana, came home one day after a day at the town’s carnival, just a few blocks from their house. As Jenni opened the front door, she noticed a folded piece of paper that had been slipped underneath the door. It was a letter, and she immediately noticed the signature markings of the powerful gang, the same one which her ex-partner had been a ranking member.

The message reeked of hatred and death threats. The letter was addressed to Jenni but contained the names of her two children as well as her parents and their addresses. The message was clear: “If she (Jenni) talked to authorities on her ex-partner’s behalf, her children and parents would be killed.” She knew that hurting or killing her family was the worst possible sentence that the malicious gang boss could order, and Jenni felt that she would be killed as well.

Ricardo

Jenni met Ricardo, her ex-partner and father of Yojana, five years ago after graduating from high school and planning to attend the university. Ricardo was smart and had money, although Jenni didn’t know the source of his income until after the birth of their daughter. He suddenly disappeared and Jenni didn’t hear from him for over a month. When he finally called her, he told Jenni that he was a gang leader and had lost the trust of his group when he failed to deliver a loaded truck full of drugs, mostly cocaine. The truck was stolen during a pit stop at a gas station. While they waited, his accomplices were shot dead and thrown out of the truck. The gang members suspected Ricardo of colluding with the suspects, probably members of a rival gang. Jenni was shocked and feared for his life, as well as hers. He told her that she would not hear from him again.

Ricardo drove his car from Honduras to the U.S. with the plan of turning himself in to the Border Patrol at one of the Mexico/US border checkpoints. He avoided detection from delinquents looking to rob migrants until he crossed into the Mexican state of Veracruz. He sensed that he was being followed which prompted him to abandon his car and complete his journey by hitchhiking. He entered the U.S. through a border checkpoint, and within a week he was in court, pleading guilty to charges of narco-trafficking. His lawyers requested leniency for Ricardo in exchange for information that prosecutors could use against other prisoners, many of whom were gang members from Honduras, the same country as Ricardo. For now, Ricardo was safe but not completely out of harm’s way.

Six months later, Ricardo sent a letter to Jenni explaining what had happened and asking her for forgiveness. He had deceived her but he promised that he would take care of her and his daughter upon his release.

Jenni was relieved to know that Ricardo was safe but knew that he couldn’t return to Honduras while he was on the gang’s hit list.

When Jenni received the threatening letter, she realized that the gang members had learned that she had been in communication with Ricardo. But she didn’t know how they knew. The only explanation was that her friend, Miriam, whom she had confided in, had told another gang member. She didn’t think that Miriam would tell anyone since her own brother had been a victim, killed by the same gang members for reasons which are not clear.

But now, Jenni had to leave and time was of essence. She contacted her sister, Stefany, several miles away and asked her to take care of her 11-year old, Rolando José. He would stay with Stefany while she traveled to the U.S. with her daughter. He would be safe, she thought, since he was not Ricardo’s son. Her sister had just moved in with her boyfriend at another location where not even her parents knew the address. Stefany and Jenni lived in constant fear since the rape of their older sister, Katrina, by gang members a year ago. Katrina was now living in the U.S. as an asylum seeker, and Jenni, upon entering the U.S. would also ask for asylum, and to live with Katrina.

Jenni contacted the local police even though she knew that they wouldn’t be able to protect her against the gang proven to be more dominant and powerful. But her sister’s case had taught her to denounce the threat, even if for just documentation purposes. The police advised her to leave the country for her and her children’s safety.

Jenni’s mother helped her collect a few thousand dollars, and early one morning, she and her daughter took a cab to the central bus station with only a shopping bag full of essentials. She hoped that their journey would be swift and, if not comfortable, at least tolerable.

The Journey

But Jenni’s luck became unmercifully bad, and relentless during her daunting journey through México. The coyote or smuggler that took them through the notoriously dangerous zones drove an old car that eventually broke down along a deserted road. The smuggler called his boss, and when help was on the way, a car with a group of four men stopped behind them, drew their guns and demanded money.

Jenni, her daughter, the smuggler and three others: a teenage boy, and a young couple, were taken to an undisclosed house, in a rural area not too far from the US/México border. Jenni had no idea of its location, but she remembers a dirt road, the seamless semi-desert, cacti and brush fields, and no houses. They were taken to abandoned house with no running water and electricity and an outhouse several yards from the house.

As the morning emerged, Jenni saw through the front window a soft light and then, four men with guns, a stark and evil presence that sent a knot to her stomach. They wore dirty clothes, were unshaven and each had scraggly black hair. Jenni, her daughter and the others, frightened and stressed out, pretended to be asleep. The men demanded money and not just a few thousands of dollars. They were the Golf Cartel and Jenni felt that she and her daughter would not survive the ordeal. Her heart was weak; she was exhausted, but her daughter gave her the strength that helped her deal with the gang members, assuring them that they would do everything possible to settle the matter without they killing anyone.

The smuggler negotiated a money drop between his boss and the cartel members. In exchange, they would drive everyone back to the main road.

Everyone was relieved beyond comprehension when the cartel members dropped them off near their stalled car. Night was falling quickly and they started walking northward, ignoring their thirst and hunger pangs. After a short walk, a man in a pick-up offered to give them a ride to the nearest town. They felt that he was an angel from heaven, and after about an hour’s ride, they arrived at a small town. The smuggler managed to borrow a car from a friend and drive the group a hundred miles toward the Rio Grande border. They begin to walk along the shallow part of the river until the smuggler pointed them toward a canoe hidden in the bushes. They carried the canoe into the water, and carefully climbed aboard, first Jenni, her daughter, and the other woman, then, the man and the teenager. They paddled across the river, and were soon stepping on U.S. soil, feeling as though they had trampled across the entire planet. They started walking eastward on a country road. Jenni prayed that a Border Patrol agent would appear and take them to the checkpoint. When the patrol car parked in front of the group, suddenly, their relief made way to an acute thirst and hunger. Once inside the patrol vehicle, Jenni spotted a plastic bottle of water beside the driver’s seat. She gently asked the agent for a drink of water, but he quickly responded that he didn’t have any, and hid the water bottle under his seat.

Once they arrived at a Border Patrol checkpoint, standing outside as they waited for the agents to begin the documentation process, the teenage boy noticed a half-filled water bottle on the ground. He motioned to Jenni that he would share the remaining water with the group. He poured water into the tiny bottle cap, and one by one, each took turns casting water drops on their scorched lips and tongue, carefully and ceremoniously. It was a moment of joy for Jenni who was struck by the generosity and kindness of a teenager.

Honduras

Deisi

Summary: Deisi was a victim of domestic violence in her country of Honduras. She endured a torturous, brutal relationship with her partner (not the father of her child) for three months. He tortured her physically and psychologically; in different days he would beat her by kicking her, throwing her against the wall and to the ground, and choking her until she almost passed out. Other beatings, included cutting her face with a saw, and, drunk and on drugs, shooting at her, barely missing her legs. She began her trip to the United States on Jan. 2, 2017, and with her daughter and a friend, arrived at the border on Feb. 14.

Deisi’s Story

Deisi felt as though her dreams had come true the day that Enrique asked her to marry him. She was 18 and he, 21 but had a relatively good paying job at a coffee plant. They rented a house, simple and cheap, and Deisi became pregnant. They decided to get married after the birth of their child.

Three years into the marriage that became too “demanding and difficult,” Enrique walks away, leaving Deisi disillusioned and solely responsible for their daughter. Deisi moved in with her mother and three of her siblings, confused and worried. Enrique begins to visit Deisi presumably to be a father to their daughter, however, his real motive was to take their daughter into full custody, regardless of Deisi’s objections. Thus, Deisi refuses to allow Enrique to see their daughter, causing a strain in the relationship between Deisi and Enrique’s families. Soon afterward, Enrique’s mother refused to accept their daughter as her grandchild.

Juan

Deisi met Juan through a friend of a friend. He asked her to move in with him, which, considering her options, seemed like a good idea. She was unemployed and had no resources other than her family to support her daughter.

Juan was a quiet but troubled 28-year old. He was known around town as a violent drunk but a good worker. Juan and Enrique worked at the same coffee factory and although they get along together, Juan despised Enrique, blaming him for having “stolen” Deisi from him and the jealousy rage that he endured during the time he and Deisi were married. Deisi didn’t know about Juan’s jealousy until later when Juan began to hurt her. Perhaps, that’s why he turned against her, she thought.

During the three months that they lived together Deisi and Juan argued and fought every day. At first, they were about Juan’s indulgence: drinking and socializing every day with his small circle of friends. But the arguments escalated and became increasingly more intense. Juan prohibited Deisi from going out anywhere except the grocery store once a week. He took away her cell phone so she wouldn’t speak to her family and friends. And, he disallowed visits from anyone other than his friends.

Every day was a repeat of the day before until Juan’s aggression included attempts at seriously hurting Deisi; perhaps, his motives were to kill her.

Deisi couldn’t escape Juan’s beatings because he would strike at any moment without any provocation. He punched and kicked her repeatedly, throwing her to the ground or against the wall. One night, while she lay sleeping, he choked her until she almost passed out. There were several near-death instances caused by Juan’s violent (and drunken) tantrums and persistent rage: the hand-saw to her face, leaving a scar on her right side of her face; the shooting with a rifle that barely missed her legs as she ran out of the house, screaming for help. Many times, Juan’s friends were there to “save” Deisi from the harrowing torture that surely would have ended in tragedy. And, the following day, Juan had no recollection of what had happened. He refused to admit to his violent aggressions.

Eragdi

Deisi’s pleas for help were ignored by her family and friends. But her brother lent her the money to purchase a cell phone. Now she was able to seek help that would enable her to leave the abusive relationship. Through the social media, she was able to contact friends and one of them, Eragdi, agreed to help her “escape” from Juan. But if she stays in her home country of Honduras, Juan will find her, she thought. Her only option is to journey to the United States. Eragdi decided to leave with Deisi and her then 5-year old daughter. The two women and the daughter walked out of the house carrying small bags to show the nosy neighbors that they were going shopping. In fact, it was the start of their long, six-week journey to the United States.

Honduras

Rosenda Nely

Summary: Rosenda’s life in one of the most violent cities in Honduras had been chaotic and overwhelming. She was a victim of domestic violence, and after the divorce, her ex-husband, the father of her young daughter continuously harassed and stalked her. She was also mugged at gunpoint by thieves on motorcycles. She and her neighbors are gripped with fear ever since the town was overrun by a powerful gang and then, after a serious, prolonged gunfight, and then, another one. Many innocent bystanders were killed while caught in the crossfire as rival gangs claim ownership to the lucrative illicit business like extortion, kidnapping, and running drugs. The current gang leader, a powerful man with a ruthless reputation now has a huge mansion in the neighborhood, and well-armed bodyguards. But of all the violent experiences, none compared to the one she lived in confrontation with one of the gang leader’s bodyguards, the husband of her cousin, Sonia. He threatened her, that she would be kidnapped, violated, physically hurt, and her three-year old would also be targeted. Like everyone else, she couldn’t count on protection by police since they are “owned” by the gangs. She cannot plan on a safe, secure future for her three-year old because of the violence and threats. Her only option was to flee her country, which she did with her daughter, and only the clothes on their backs.

Rosenda’s Story

Rosenda’s walk to the corner store two blocks away is like treading through a minefield. Except that, instead of fearing the fatal step, she looks for signs and sounds of gun battle; dodging the bullets with the careful vigilance of a hawk. She feels exhausted, and it’s not quite ten in the morning. She believes her town is gradually becoming her prison. She feels as though her whole life has been a prison. At the store, she meets up with Sonia, her cousin whom she considers her sister. They chatter as if they hadn’t talked for a long time, but actually they call each other on their cell phone each day. They share many interests since they grew up together. They even married their boyfriends almost at the same time. Unfortunately, they also suffered similar domestic violence in the hands of their repressive husbands. They all seemed happy in the beginning of their marriages, but life in a small town in Honduras hardens the men and makes the women powerless and vulnerable. Without a secure employment or even employment opportunities, women’s lives teeter on instability, both economically and socially. “The woman stays at home to take care of her man,” the husband, Salvador, would remind Rosenda of her place in life.

Rosenda doesn’t remember when the beatings started. Perhaps, the rough sex led to the casual verbal insults, then, the face slaps and hair pulls. Rosenda’s beautiful long hair was perfect for Salvador’s torturous aggressions, amusing himself by pulling Rosenda by her hair. Life became a drudgery full of physical and emotional pain.

Salvador left town when he realized that “men with guns” were looking for him. He owed money to a wealthy, shady landlord and his debt, about five years old, had to be settled. But Salvador didn’t have the money. Rosenda felt relieved but troubled. How was she going to provide for herself and her 3 year-old daughter, Kimberli?

Sonia and Juan

Sonia’s marriage began to deteriorate right after the birth of their first child. Her husband, Juan, had been unemployed for several months, and for sustenance they relied entirely on the charitable generosity of her family. Juan hated their dependence on her family, especially since his father-in-law looked down on his inadequacies in providing support for his family.

But Juan’s luck would change when Don Robles and his horde of bodyguards and servants moved into the big mansion on the hilltop, just above Rosenda’s community. Robles was the powerful cartel leader, the latest crime boss to take over the town after running off the previous criminal organization. Juan sought employment as a bodyguard and was quickly hired. Don Robles was a notorious kingpin known to Hondurans as a murderous, heartless narco-trafficker that gives orders to prey upon innocent people and kill his competitors so he can amass capital and boost his powers. Juan became one of Robles’ “soldiers” and Sonia’s fear was elevated now that he owned a gun.

Juan became the loyal follower, a brand of soldier sought after by vicious cartels. His increasing absence from home gave Sonia some relief from his constant bickering and verbal abuse.

Rosenda and Sonia

While he was gone, Rosenda visited Sonia and together they consoled each other. Joyful, happier times returned to their lives. But sometimes Sonia could not accurately predict when Juan would return home, and inevitably, he would show up when Rosenda was in the house visiting with Sonia. Juan grew suspicious of their friendship, imagining that they were plotting against him.

But Rosenda would continue to visit Sonia. She would leave through the back door as soon as Juan pulled up in his company car. Branding his gun and a macho attitude, he was a true-blue cartel soldier.

The beatings and verbal assaults became far more intense and frequent between Sonia and Juan. Rosenda became deeply worried and decided to confront Juan. But she quickly learned that this was a mistake. Juan turned his aggression toward Rosenda, and on one occasion pointed the gun at her head and warned her never to return to their house.

From that point forward, Rosenda helped Sonia design a plan to move out of the house, to an undisclosed location, where Juan would not find them. But, their hopes were dampened when Juan realized their plan. One of the neighbors, a woman who despised Sonia, snitched on the two women when she overheard their plan to move out the next day.

Rosenda Becomes the Hunted

The threats were serious and relentless. Juan would call Rosenda several times a day, delivering verbal assaults. He threatened to kidnap her and her daughter, hurt and rape them, and kill them. Then, he would drive by her house, park his car and wait. He would send his fellow soldiers to guard the house, preventing Rosenda from leaving.

Rosenda kept vigilant and as soon as she noticed that no one was watching, she packed a small bag, dressed her young daughter and moved in her mother’s house.

A few months later, Rosenda sits quietly with her daughter on her lap, awaiting orders from the U.S detention center officials on what she will do next. She made it to the U.S., but fear still overwhelms her deeply.

Guatemala

María

Summary: María, 24 yrs. old is from Guatemala and her first language is Mam although she speaks Spanish well. The father of their five year-old daughter, Vergilio, abandoned them a year after her birth. She suffered physical and psychological abuse in the hands of Vergilio. His mother refused to accept María’s daughter as her grandchild. Her father is an invalid; he had a stroke and is paralyzed on one side of his body. He needs constant care and her 17 year-old niece takes care of him. María’s hometown is unsafe, especially in raising her 5 year-old as a single parent. A year ago, two young women were killed for unknown reasons; three years ago, her friend, also a young woman, was killed and her body dismembered. Only her head and a hand were found. Women are vulnerable in this community where men believe they can murder them without any repercussions. The police authorities are known to be incompetent and lacking in resources. None of the murders was solved. The fear and lack of employment opportunities have compelled María to travel north to live in the U.S.

Maria’s Story

Two slight figures stepped down the stairs of the passenger bus in a crowded downtown bus station in a city in central part of México. María, 24 years-old and barely 4’7, her daughter, Fabiola, who is 5 years-old but appears to be one or two years younger, make their way to the central hub of the station. Hungry, tired, and confused, the mother and daughter have spent seven days and several bus stops into their trip toward the U.S. border. A long way from their Mam-speaking community in Guatemala, they’ve reached the midway point. But this bus stop seemed the most difficult because all of their money and food were spent. But, María, determined to reach the East Coast of the U.S. to live with her older sister and brother-in-law, begins to scour the crowded bus station for food on the floor, the trash bins, anywhere for anything that her hungry child can eat.

María was accustomed to regular hunger bouts in her hometown, a small rural community in Guatemala where her culture and language have deep roots amongst the Mam people. She lived in the rugged, mountainous region where her mother, father, and two older siblings sustained themselves with homegrown vegetables and animal products. Their complete reliance on the weather and soil conditions created a subsistence living, and many times during the year, the family had to stretch out their basic essentials of corn, beans, milk and eggs to a bare minimum.

María approached the local street vendors as the first of many strategies that she devised. She asked for handouts for her very hungry child. The gentle sweetness of her voice seemed staged at first but the smooth resonance and kind demeanor in her expression is the normal voice that she uses when she speaks in Spanish. In her native language, Mam, her voice becomes less exact and more variable in pitch and tone, in keeping with the cadence of her indigenous language.

Some of the vendors quickly brushed her aside, others slipped a small portion of a taco into the hands of her child, or a piece of fruit from the fruit cocktail cup. But María wouldn’t touch any of it until her child was satisfied. Then, it was her turn.

María grew up as a well-loved child whose mother cared for her deeply. Even though her mother died when she was nine, she spent all day by her side, learning the chores, responsibilities, how to make small miracles from bits of morsels of food to feed the whole family, and how to defend yourself from cruelty and deception, especially from discontented neighbors and strangers. These were the skills and the lifestyles passed on from one generation to another, from grandmothers to mothers to daughters.

Leaving “El Corte” Behind

María grew up wearing the traditional dress called "el corte," consisting of a colorful, multi-reddish skirt made from two rectangular pieces sown together then folded over and around her waist, and a similarly colorful cloth belt tied to hold her skirt together. The blouse was simply embroidered, white and tucked inside the skirt. She wore el corte everywhere she went except when she was asked not to do so, like inside the house she was hired to clean. That was the case at Doña Marta’s house in Malacatán, near the México/Guatemala border. She had heard from her friend, Rosenda, whom she worked as their housekeeper, that Doña Marta needed another maid. María took her daughter wherever she worked, and Doña Marta allowed both of them to stay and live in the house for which Maria was very grateful. But Doña Marta told her not to wear el corte, and Maria had no choice but to remove it and become a common housekeeper like all the rest, without a name or appearance that once identified her as the person she really was.

Leaving Guatemala

But leaving her culture and language behind was only the beginning of a new life for María. The choice to stay or leave Guatemala for the U.S. was the hardest decision to make but once she made up her mind, it became easier. She felt that she couldn’t go back to her rural community, a five-hour bus ride from Matacatán because of lack of employment opportunities, and although she loved her father, he was completely reliant on her niece’s care. Besides, the violence, especially against women, was a major factor in the need to create a better future for her daughter. Doña Marta was a good employer but her demands were increasing as Maria’s skills improved. How could she send her daughter to school, she thought, and still work overtime for Doña Marta? She felt homeless, detached from her community and had so little to give to her daughter. Her sister and brother-in-law promised to help her settle in once she arrived.

It took María and her daughter 15 days to travel to the U.S./México border from the Guatemalan border. Awaiting asylum proceedings at a detention center in Texas, she has no regrets. Yet, when will she realize that a new life means leaving behind everything she has ever known, to be who she is. How will she come to terms with her new life while her past is mostly made up of memories and dreams?

See related posts in this blog: MAPS AND GRAPHS and SNAPSHOT.